Period poverty. Yes, it is exactly what you may hope I am not talking about, but it is time for women and men to remove the stigma and support our young ladies. Don’t stop now…read on! You may be surprised to realize that this issue is an equity issue taken up by many states.

Period Poverty is a legislative hot topic in Hawaii and several other states. Period poverty is a term used to describe how the inequitable costs of menstrual products affects girls, women and families in poverty. Essentially it means with all of the competing financial stressors on struggling families, having a daughter or daughters who reach puberty and experience their menstrual cycle becomes another added challenge. And perhaps you haven’t thought about women and girls in poverty who are homeless or incarcerated.

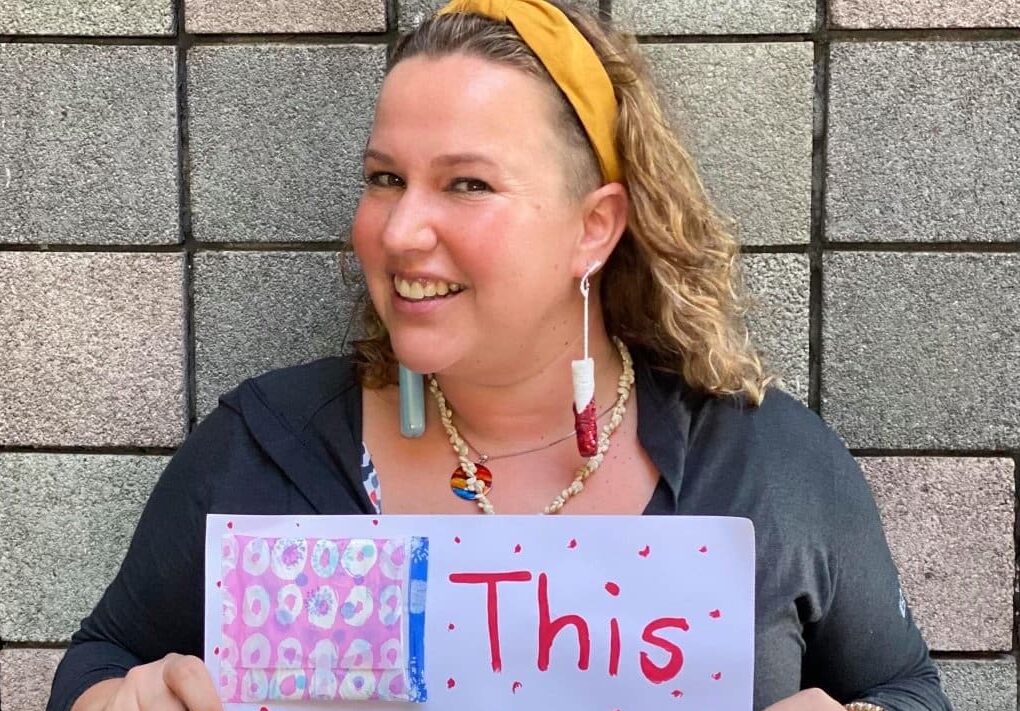

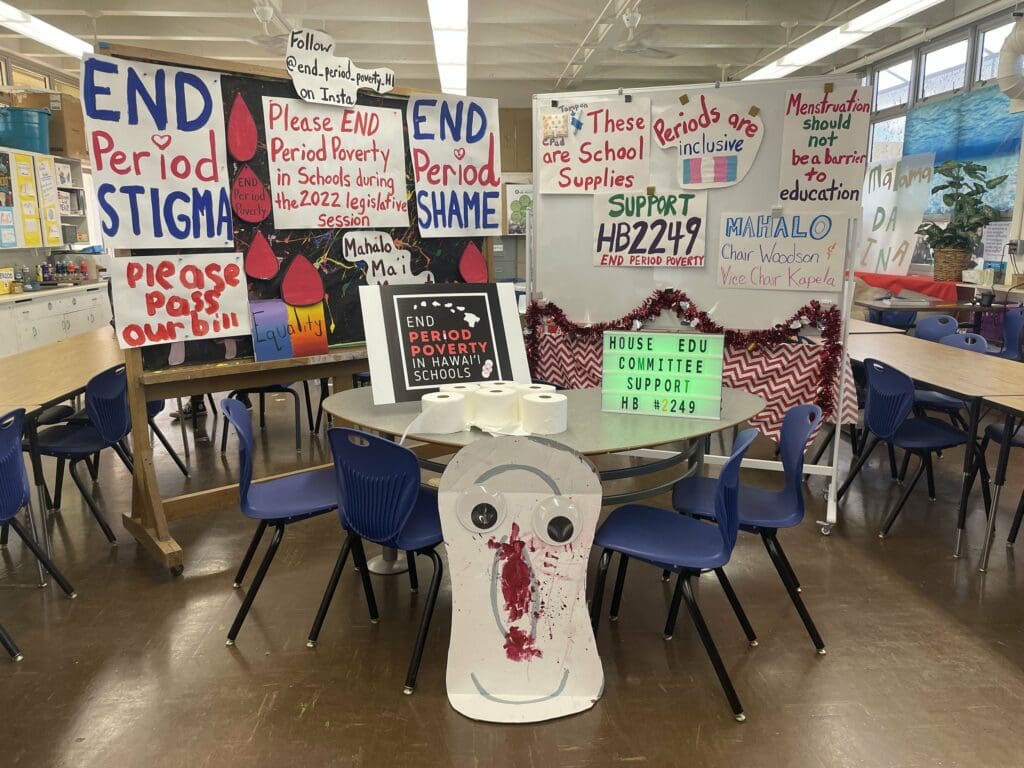

Rather than a celebration of an important right of passage that half of our global population experiences, which is a precursor to procreation, starting a family, and life itself, this natural experience is a taboo conversation often avoided. What you may not realize is that this issue avoidance creates a sense of shame for girls, especially girls of poverty. While some school districts and states have come to realize that menstrual products in bathrooms should be just as ubiquitous as toilet paper, or for that matter urinals in men’s bathrooms, many leaders still don’t get it. This is why I sat down with an equity-minded teacher – Ms. Milianta Laffin (affectionately called Ms. Mili by her students) who has jumped into this policy issue with two feet bringing along with her both female and male teachers to better support girls in the interim, until such policies and practices can become the norm.

*See Learn More Links at the end of this interview.

INTERVIEW WITH HAWAII TEACHER MILIANTE LAFFIN, aka MS. MILI

Christina:

Why is period poverty a legislative matter?

Ms. Mili:

I think for years teachers have been the ones to willingly hand out period products that our kids need. I have definitely been that teacher who has given out my last tampon. And then I find myself at Target needing one, and I wonder ‘why don’t have I have this?’, and I’m like ‘oh yeah, I gave it to one of my kids’. Teachers are always big on community care, but we know from policy history that good government can support community care. And if we can legislate the funding to make this happen, it’s just a great way to keep our students in the classroom. We know the absenteeism rate for students who don’t have access to safe period products will keep them out of the classroom a few days a year. And those days are so critical. And if providing products keeps them in school, that’s good government and good education policy.

Christina:

Why can’t the Hawaii Department of Education just purchase this along with its toilet paper order?

Ms. Mili:

For myself, and I’ve had some great conversations with Catherine Payne at the State Board of Education, I do see this as a Title IX issue, but I know there are complexities to that as well. Because yes, I would say that when we look at what we provide for bathrooms already, some of the feedback has been ‘well we put urinals in the boys bathroom and technically they can pee in the regular toilet, but we supply this for boys and men. So how are we being equitable in the way that we allocate products. We have also just learned that every school functions differently in the way that they support their nurses. So some nurses might have a budget for products and some might not, and this is a site-based decision. Just to make sure that we do have equity, it’s got to be something that is a line item provided for every school in the state budget.

Christina:

Why is it such a big deal for girls to have to go to the nurses station?

Mili:

Because we don’t want to pathologize periods. There’s nothing wrong with periods. It’s ok to have a period. It’s a healthy, normal process. If we didn’t have periods we wouldn’t have humans. But when you force a child to walk across the campus, probably already bleeding out and uncomfortable, and to go explain it to another adult, you know we have these adult gatekeepers. Even more time is taken out of the classroom. It’s going to be uncomfortable, and a lot of our students actually wouldn’t go. So by having these products in menstruation stations in the classroom or provided in the restrooms that saves time for our students and makes our students feel supported. New data from the period report from various period movement organizations say that 57% of students nationally don’t believe that their schools care about them if they don’t provide period products. And we’re seeing right now epic levels of students not feeling a sense of belonging on campuses, and by having these products available we can also help rebuild that sense of belonging. It says that they are fine, that they are healthy, that they are wanted in our classrooms.

Christina:

The language is very intentional…period poverty. So tell me a little more about the poverty side of this issue.

Mili:

I’ve taught in Title I public schools for sixteen years, and if you are a Title I school that is saying that over half of your typical school population can’t afford a school lunch. So if you can’t afford a school lunch there’s a good chance that you are in a family that can’t afford these products. But we’ve also learned from conversations that because we serve a high military population, perhaps mom is deployed and students are afraid to talk to dad about period products. We also have students in foster care placements who are just afraid of asking for anything else even to meet their own needs because you don’t want to upset that placement. There are a lot of reasons why we may not have access but we have to be accurate about the language. Language is so important because it puts the gravity on that situation.

The new data we have in Hawaii from the State Commission on the Status of Women and from Ma’i Movement said that there is even more need than we thought. We now have period poverty data from November 2021 that says that over half of our students at some point have not been able to get their products when in need. I think that as adults, that should really be chilling that we have those numbers and that we know that it’s an issue and that it’s our job as adults to fix it now. Also, we have to be careful with poverty, the idea of saying ‘you have to be deserving enough to get something.’ I serve middle school students. They can’t have jobs. They have no control over their economic situation. I always say, if a student walks into my classroom without a pencil, I’m going to give her a pencil so she can learn. We really have to understand that period products do allow students to facilitate continued learning and that’s why they should be provided.

Christina:

This is not an easy conversation. Whether it’s men thinking they do not need to be part of this discussion or even the fact that even women shy away from having the discussion. If the discussion is not happening, and is not being supported by women what do we need to do to change that? How do we change the stigma about something that naturally happens to half of the world’s population?

Mili:

You know it’s a tough one! Part of it is just radical truth. Radical truth and radical honesty. I’m trying to be better at scientific wording. I’m a science teacher by training and so it never occurred to me that if I were to say out loud at a hearing about shedding uterine lining, I didn’t think people would go white. I didn’t think they would freak out and get uncomfortable with the conversation because that’s the way that I taught. That was something that was very interesting to me because a lot of people don’t talk like that or talk in euphemism…the curse, aunt flo, or whatever you call a period. That can also be confusing to our students who may not understand what people are referring to. Language is critical in these conversations.

And I do put some of the responsibility on women who don’t speak to their partners. I have to say that my partner is a rock star! He goes and buys tampons and he will make sure if it’s for a heavy flow or a light flow. We have these open conversations and that’s how we start that [change]. One of the secrets at my school right now is, so we have these menstruation care packs that have been funded by Donors Choose and I try to put in a few different types of pads because kids are learning. Heavy day or a low day. I love when they come in and say ‘Ms., it’s a heavy day,’ and I say ok then we will get the thicker pads. The best boyfriends on campus now keep one in their backpack just in case their girlfriend needs it.

It’s such a simple thing, but there is such a radical movement. If we are educating our boys, imagine what kind of fathers and partners they are going to be. Understanding and having empathy for what menstruation is and what women need and are going through. In traditional secondary education we have separated…girls go here and boys go there and you learn about separate stuff. There has to be more inclusive learning.

Christina:

So what about required training for teachers who are teaching students from the fifth grade upward?

Mili:

In my dream, I think definitely. There are teachers who come to me and say, ‘Mili, I want to talk about this but I’m so scared.” And another thing that teachers have said is that talking about menstruation would be listed under controversial issues for the department of education and there is such a fear of making sure that you are informing [parents] if you are going to use that language. I think more teacher training would get rid of some of that teacher fear. I am a big believer in non-bleeding allies. That is what we call our dude supporters, that think that they need to be having some of these conversations too. Being a child of the 90s, period humor and slapstick comedies about periods… there was a stigma that came with that. Just because I’m having a bad day doesn’t mean I am on my period. We have to counter those stereotypes. Teachers are professionals and they want the newest and best possible training possible to make sure they are doing things right by their students. Administrators who want to be leaders in this area can facilitate that by making it ok to talk about and leading in that way as well.

Christina:

There is a significant gender equity issue here, in terms of what women and girls have to pay for in terms of products. And it’s part of a long list of economic and health care impacts. Now as girls grow up and into these systems of disparities, they are faced with figuring out how to pay for products that are expensive but necessary. They don’t have a choice. We know they are opting for unhealthy alternatives that are not good ways of caring for their bodies. What do you have to say about some of those inequities and making an equity argument around this issue.

Mili:

I think it’s hard. I started to find my voice when I turned 30. I think I was socialized as a very compliant female. ‘Don’t ask questions, don’t cross what your leader says.’ So you learn to go along with things. And so for generations women have just been like this is a hush hush thing, to be talked about privately, not have this conversation, don’t rock the boat. I especially think that as women have sought professional parity to men it has become an issue of ‘is it a weakness to talk about this? You can’t make men uncomfortable.’ What we’ve done in the past is try to get into a man’s world. And the idea now is ‘no, it needs to be an inclusive world.’ Just the idea that I am not going to hide how I am feeling or I’m not going to not address this for their comfort.

I also think there are other cultures that are so far ahead of traditional American culture when it comes to equity. In Japan you can take menstrual leave. So if you are having period issues and need to take days off that is something that, you know we don’t even have family leave and that’s pretty basic. It’s gotta be something that women band together to work on. The other part that has been uncomfortable in this bill is being told, ‘oh that’s a women’s issue, that’s a girls’ thing’. In some of the opposition testimony we’ve gotten is ‘well I’m a guy, why should I have to pay for this product.’ Well, you are alive on earth and that is thanks to a period, so there!

I believe my social justice work as an educator is also about instigation. What I can do with the privilege that I have is to instigate some of those conversations and perhaps it will be for someone else to finish. But I don’t mind starting those conversations. At the end of the day, this is to make my students’ life better.

Christina:

I can’t help but ask the question around the religious bent to this. If you read the book the Red Tent, there was this separation of women because there was something different, something happening to them, that made them untouchable and unclean. Religion also has played a role in stigmatizing a woman’s menstrual cycle. There are different observations depending on religion. How does that play into the conversation, because it can also be a religious taboo?

Mili:

That is interesting. You know I was raised evangelical. I was even homeschooled for a while because of my family’s religious views. I was actually raised as a messianic Jew. And one of the things I’ve learned in my communication style is very Jewish – it’s that interrogating of thought. If I am going to bring up an issue, I’m also going to try to solve it. The idea is that we have to talk it out first. I have to be careful. The majority of students that I serve come from different parts of the Philippines. One thing I realized, a pitfall you don’t realize when you first get started, was what families say about tampons. I had a mom come to me that was terrified that her daughter would not be intact for marriage. She wanted to protect her virginity. She believed tampons would take away her virginity. As a scientist, I want to be sure I am providing accurate information. As a teacher who does not have a signed waiver to talk about that with a kid, that gets tough. And so, how do I honor these families that I have worked so hard to build relationships with. I’ve gone to their family events, I’ve gone to their churches, how do I respect that part but still give accurate information. I will say that for the menstruation station we have gone mostly with pads just to make sure we are not treading into that space, but I also hope that as we end the stigma, more of these conversations can happen.

Christina:

I’ve watched you over these past few years and your policy voice has grown. You know that I am a big proponent of teachers as policy leaders. How do we get more teachers comfortable with using their voice? You took on an issue that is a passion issue for you because you see this as an equity issue. And every teacher has that opportunity to find that policy matter that they are passionate about. How do we get more teachers leading through policy? Policy can be intimidating, but like you said in the Maestro Vibes podcast, you are not a policy expert, but you realized that was how this had to be addressed.

Mili:

That’s a hard one because I feel like while I am willing to do this work I don’t push it on anyone else…just because it’s lonely work. Social justice work in education, you will often find yourself standing by yourself. It’s not easy. Administratior support, that’s important. I look like a rebel teacher and that’s not always a teacher that’s wanted on a campus. But, whatever choices that I make as an educator I have to be able to sleep at night. I live my values and to not speak up to me would be far worse because of what students who don’t have these period resources are going through. But it’s tough. I have known several teachers who have left the classroom and gone into the policy space, who have gone to work for non-profits because their activism was not wanted in the classroom, wasn’t wanted at the school.

It’s uncomfortable when we bring equity issues because leaders who maybe have a blind spot are suddenly very uncomfortable because they believe they should know all the things. I’m a big believer in Maya Angelou who said, ‘we can’t do better until we know better, and when we know better we do better.’ We have to be comfortable with lifelong learning. We have to be able to say if we have equity blindspots, then the right thing to do as a leader is be okay with working on addressing them. To understand that rebel teachers like me…what I need from administrators and leaders is to see my passion and to understand that my passion is not intended to undermine what has been built on the campus or district. But again, my job is the students and that’s who I’m fighting for and speaking for because so often the students I work for have often been…well their voices have been left out of the conversation.

Elizabeth Warren says, ‘If you don’t have a seat at the table, you are probably on the menu.’ And Shirley Chisolm told us that ‘if you don’t have a seat at the table, you bring a folding chair.’ So when I’m dragging those folding chairs and moving those tables around with the privilege that I carry, especially as a white educator, then I am bringing my students to the table and making sure that they are in the spaces that people do listen to them. It’s hard, because I do want more teacher activists, and I want teachers to join that’s why I am so active on twitter. Twitter is my virtual teachers’ lounge where I can find other teachers like me and connect with other people who are also passionate about policy.

Everything we do as an educator is political. From funding to our building facilities. All of it is political. It’s hard for me when I hear teachers say I don’t do politics. Politics is dirty. Well your boss does politics, and your school district does politics. It’s tough, but I am very excited to see some young administrators come forward. I’m excited about this next generation of administrators who I hope will give more space to teachers and not make ‘teacher activists’ a dirty phrase.

Christina:

House Bill 1636, Rep Clark has introduced it to exempt femine menstrual products from Hawaii’s General Excise Tax, are you involved with that as well, and what are your thoughts?

Mili:

I definitely think taxation is important. I’m kinda protective of my student activists this year because they are very excited. The taxation issue is a little more tough, especially because we have multiple vehicles moving right now, multiple bills. I’m trying to protect their energy and not ask them to testify at every hearing. I have lone students who want to submit written testimony. The oral testimony is way more tricky. One of the frustrations we found, for example when you submit testimony in Hawaii, there is a capitol.gov account where you have to confirm your account. Well the students’ gmail accounts for the department of education do not get the confirmation emails. So if I want my students to testify they have to confirm from their email at home. And that’s a hard thing for middle schoolers. I am working mostly with twelve and thirteen year olds.

I will also say, the students who started this work are now sophomores in high school. Each year they’ve educated the underclass about this policy that is moving forward. This year especially since we had that virtual gap year it was harder to have that co-educational model to keep the activism moving. We are trying to focus our energies on the products in schools, but I will say with Ma’i Movement and myself we are pushing the adults to put in testimony on that taxation side. Because the amount of money that women pay on the whole pink razor versus blue razor is beyond! But also the state is uncomfortable changing the revenue policy because that’s money lost. When we first presented this at a hearing in 2020 we were told, ‘well if you get rid of the pink tax, Hawaii loses $1.3M.’ My answer to that is ‘well that’s an inequitable system, so find another place to get the money instead of using women and girls as those who have to fill the coffers of the state.’

Christina:

Ms. Mili you are an incredible example of voice to other teachers in the state. I celebrate you, I applaud you, and I encourage you and support you to keep after this. This has been a taboo topic, and while it can be uncomfortable, we have to talk about it. Along the way, we can figure out language, figure out how to put the words around this, but the matter has to be talked about because this is an equity matter and our young girls are not being supported. Thank you for your leadership! Other teachers are watching you and learning from you. Thank you for your teaching service, our students need you. Social justice should never be lonely.

Mili:

Thank you for sharing your platform on this important issue!