Looking back in retrospect to my childhood during the 1970s I can remember the way in which women around me began to explore their voice and started to question assumptions about gender differences. I repeatedly heard women tell girls that they could do things that they themselves had never done such as aspire to jobs held typically by men. These included political office, policing, the law, and so on. I remember my mother coming to a parent-teacher night and on the roof outside of the classroom window was a crew of construction workers that included one woman using a heavy tool of some type. My mother gathered the mothers in the classroom and began to bang on the window until she got the female construction worker’s attention. When she looked up from her work, the room of parents exploded into hand clapping and cheering. Imagine that scene, where a room of mothers, who had never seen a woman construction worker, were so moved by that example of possibilities that they could not resist but celebrate the moment.

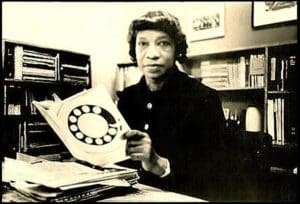

MIT Sloan School of Management recently released an article about one such woman who dared to enter a field dominated by men. She not only contributed to the field of economics and the labor market, but brought many others along with her, particularly men and women of color to whom she served as a connector to prominent faculty positions. Her name was Phyllis Wallace and she broke the gender barrier at MIT by becoming the first woman granted tenure at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Her story is fascinating, and reading about her opened up the floodgates of memories for me of all of the women who crossed my path when I was a child, seeking to support women in accomplishing many “firsts.” Even though Ms. Wallace passed away thirty years ago, her bold actions in shattering glass ceilings are important to share today because we still have a long way to go in accomplishing gender equity in the workplace.

Ms. Wallace, who was an economics expert, was hired in the 1970s by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to help disrupt discriminatory practices against women by communications giant AT&T. Her contribution to this investigation by the EEOC led to a consent decree with monetary outcomes for women who had been cheated out of equal pay, and led to groundbreaking policy changes around promotion and wage structures. There’s much more to her fascinating story, but I will let you read the article for yourself.

Ms. Wallace, who was an economics expert, was hired in the 1970s by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to help disrupt discriminatory practices against women by communications giant AT&T. Her contribution to this investigation by the EEOC led to a consent decree with monetary outcomes for women who had been cheated out of equal pay, and led to groundbreaking policy changes around promotion and wage structures. There’s much more to her fascinating story, but I will let you read the article for yourself.

What I want to do is highlight three key lessons for women from Ms. Wallace’s life. First, while pursuing her research passion, she led others to success along the way. I read in a fictional novel once a statement that has stayed with me since my college years, “People pass casually through your life, when trumpets should blast.” Well Mrs. Wallace was one of those people that caused trumpets to blast. She led many others to success along the way and elevated the readiness of many including black researchers and scholars to continue the work of exposing the economics of discrimination. Think about the people who have crossed quietly through your life who have provided that trajectory for you.

The second lesson from Ms. Wallace’s life is a reminder to those of us who have the opportunity to lead for equity, to consider how we choose to use our position power once gained. Ms. Wallace was called a “quiet revolutionary,” according to the article. Where does your power and sphere of influence lie and to whose good are you applying it?

And finally, I can’t help but feel a personal connection with Ms. Wallace on her work exposing the economic conditions of vulnerable people in our society. She believed that by studying the most vulnerable people in our community, we gain a real understanding of conditions that impact all the people around us, and their impact on the economy.

This is a reminder of the many women who have fought for gender and racial equity over the years, upon whose shoulders we now stand. They changed our access and opportunities, now it’s in our hands to continue to advance this work and improve the life trajectory of those who today are still negatively impacted by biased and discriminatory policies.